Recently, while chatting with an atheist friend, he told me — quite enthusiastically — that he was a fan of Dostoevsky. Curious, I asked him what he thought of The Brothers Karamazov. I then noticed something that caught my attention: although he had read the book, he hadn’t truly understood what the work was about.

This is a more common situation than it seems. Many people read Dostoevsky “halfway through.” They grasp the psychological drama, the moral dilemmas, the existential conflicts — and indeed, all of that is present in his works. But they overlook the foundation that underpins all his writing: the Christian worldview.

Dostoevsky was not merely a brilliant novelist; he was a Christian thinker profoundly aware of the spiritual battle waged within the human soul. His characters live through inner conflicts that can only be fully understood in the light of a philosophy of forgiveness, love of neighbour, freedom, redemption — and evil as a concrete reality, not merely a metaphor.

The Brothers Karamazov, perhaps his most profound work, is also his spiritual testament. It is impossible to truly understand it without considering the thread of Christian faith — not merely as a backdrop, but as the very structure of the narrative.

It’s natural that this perception escaped my friend. After all, Dostoevsky was a fervent Christian, an Orthodox believer writing from the pains and illuminations of his faith. Without understanding the way his heart thought, it’s impossible to grasp all the layers of his writing. A line from the novel touched me deeply and brought me back to it in this reflection: “The heart of man without God is destined for barbarism and chaos.” Therefore, reading Dostoevsky without bearing this in mind is like reading a Gospel as though it were merely a piece of theatre. It lacks soul — and without soul, you cannot understand the meaning of that writing.

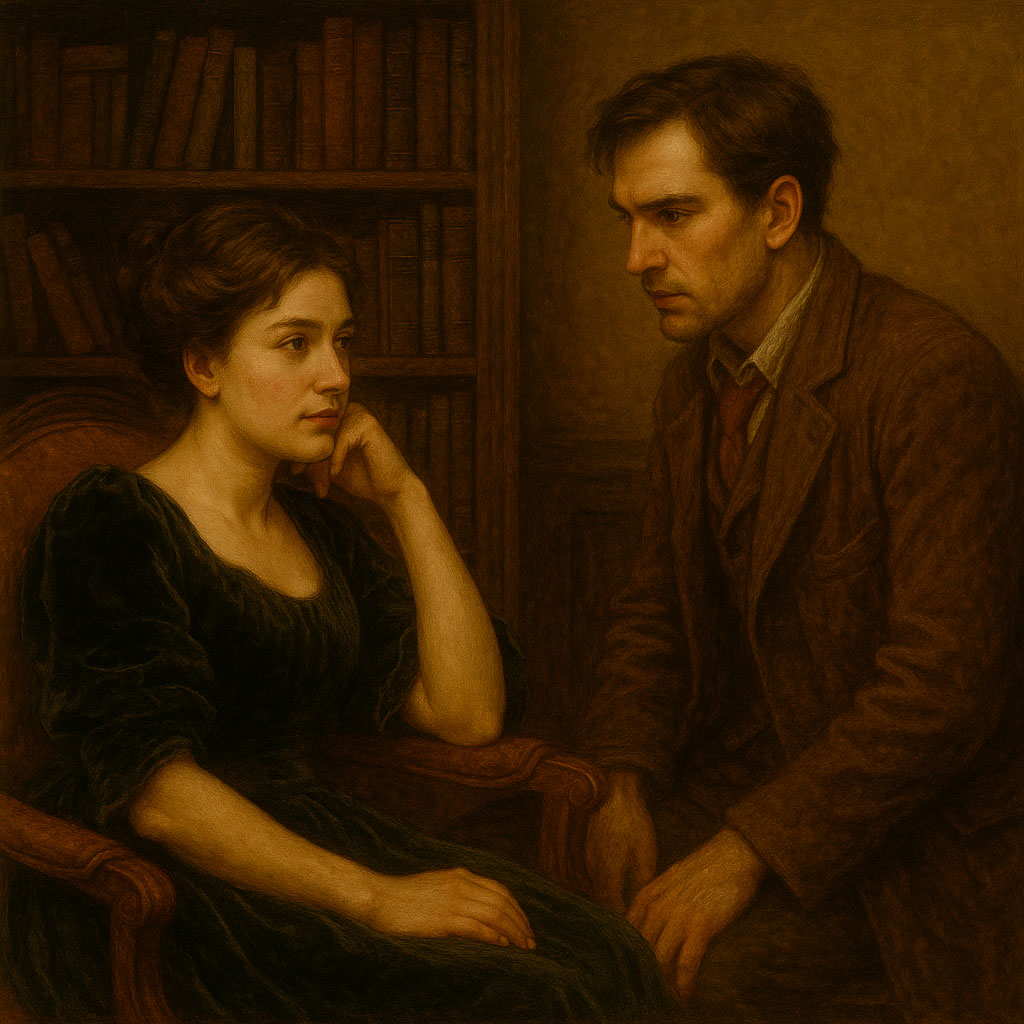

To understand the transformative impact of The Brothers Karamazov, it’s essential to know who its protagonists are — the father, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, and his three sons: Dmitri, Ivan, and Alyosha. Each represents a dimension of the human soul in conflict: the sensual and impulsive, the rational and sceptical, the spiritual and compassionate. The way these characters relate to one another — and to the world around them — not only drives the plot but reveals Dostoevsky’s conviction that it is in the encounter between real people, with their wounds and choices, that the world can be redeemed… or destroyed.

The novel revolves around the Karamazov family, whose patriarch is a man who can be described as embodying the worst of humanity. He has three sons, born of two marriages: Dmitri, Ivan, and Alyosha.

Dmitri Karamazov

Dmitri “Mitya” Karamazov, in The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky, is the eldest son of Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, a hedonistic and negligent man. Dmitri represents the struggle between passionate impulses and the quest for redemption, between the animalistic and the spiritual in human nature. He is often depicted as an impulsive hedonist, driven by intense passions, yet with a genuine heart and a conscience that sets him apart from his father.

Dmitri is passionate, impulsive, and lives in extremes. He is an elegant military officer but also an irresponsible spendthrift, addicted to women, gambling, and drink. His life is marked by inner conflicts between carnal desires and aspirations towards honour and nobility. He has a strong attachment to German Romantic poetry, especially Schiller, reflecting his desire to transcend his coarse nature through lofty ideals like universal love and justice. Dostoevsky presents him as a tragic figure, caught between “the Madonna” (spiritual purity) and “Sodom” (sensual degradation).

Dmitri embodies the body and passion in the Karamazov triad (alongside Ivan, representing the mind, and Alyosha, the soul). He represents humanity’s struggle to balance its basic instincts with the search for meaning and redemption. The prosecutor in the novel states that Dmitri “directly represents Russia,” with his mix of sincerity, kindness, and chaos. His contradictory nature reflects Dostoevsky’s belief that the typical Russian can love God even while sinning.

Dmitri’s transformation is one of the novel’s most significant arcs, marked by his journey from self-destruction to spiritual redemption.

At the outset, Dmitri lives without considering the consequences of his actions. He spends recklessly, accumulates debts, and even threatens to steal from his father, fuelling family tensions. His passion for Grushenka leads him to impulsive acts, such as publicly humiliating Captain Snegiryov. He is accused of murdering Fyodor, a crime of which he is innocent, but his reputation and past behaviour incriminate him.

His imprisonment and interrogation mark the beginning of his transformation. Confronted with the accusation of parricide, Dmitri begins to reflect on his life of excess and guilt. He acknowledges that although he did not kill his father, he is not without sin, for he has lived dishonestly and irresponsibly. A dream in prison, in which he sees a peasant woman with a starving baby, awakens his compassion for humanity and a desire for purification through suffering.

During the trial, Dmitri emerges as a tragic yet redeemed figure. He accepts suffering as a path to atone for his sins, declaring himself ready to “be purified through suffering.” This acceptance reflects a profound change: from a man dominated by passions to someone who finds hope in spiritual redemption. His experience in prison leads him to a moral conversion, aspiring to a life of goodness even while facing condemnation.

Although unjustly convicted, he leaves the trial a transformed man, stronger and committed to goodness. His journey reflects Dostoevsky’s central message about the possibility of redemption, even for those who fall into the depths of degradation. He comes to symbolise the hope that humanity, despite its flaws, can find a path to salvation through suffering and self-reflection.

Dmitri Karamazov is the embodiment of humanity’s struggle between sin and redemption, a man of intense passions who, through suffering and introspection, finds a path to spiritual transformation. He represents Dostoevsky’s Russia — chaotic, sincere, and capable of redemption — and his journey of self-discovery reinforces the author’s belief in humanity’s ability to overcome its flaws through faith and sacrifice. His transformation from an impulsive hedonist to a man who embraces suffering as purification is one of the most powerful elements of the novel, highlighting the complexity of human nature and the possibility of renewal.

Ivan Karamazov

One of the most disturbing scenes in literature reveals the nature of evil and what it means to reject God. To understand Dostoevsky’s Satan, one must first know his target: Ivan Karamazov, a cold intellectual, a humanist who rejects God not due to disbelief but out of revolt against human suffering. He argues that a God who allows pain, especially the suffering of children, cannot be good. His disbelief is not mere atheism; it is a moral refusal. For Ivan, religion is a crutch, and morality a human invention to ease suffering. He claims to “love humanity” but confesses to despising people. By denying God, Ivan loses the capacity to love his neighbour, and this loss corrodes him.

Ivan knows that “without God, everything is permitted.” His ideas torment him, gnaw at his soul, and even inspire others to commit crimes. He recognises that man needs God, but his pride prevents him from repenting. It’s not the lack of faith that condemns him, but the lack of love. Ivan cannot bear to bow before God, even though he knows He exists. It’s at this breaking point that the Devil appears.

Towards the end of the novel, Ivan, sick and feverish, has a hallucination in his room. An obese man, wearing a shabby coat, appears on his sofa. “Who are you?” Ivan asks. “I am you,” replies Satan.

The Devil does not try to deceive Ivan. He doesn’t need to. Instead, he mocks him, as though his soul were already won. He reveals that Ivan’s atheism is not merely disbelief but a hardened hatred of God. Ivan prefers hell to communion with Goodness. His atheism echoes Judas: knowing Christ, knowing He is God, and yet rejecting Him. This is the “unforgivable sin” — a heart so hardened that it rejects divine love even unto death.

Satan does not argue with Ivan. He merely provokes him, driving him to madness: “Your ideas are evil, and you know it, but you refuse to repent.” Ivan’s intellect, once his fortress, crumbles, and he plunges into insanity.

Despite this darkness, The Brothers Karamazov offers hope. Alyosha, Ivan’s brother, is the counterpoint. Humble, timid, and devout, he loves God yet fears evil. Initially, he seeks refuge in a monastery until his mentor challenges him: “Face the world and love your neighbour.” Alyosha faces temptations but his heart perseveres. He loves Goodness too much to surrender.

Ivan, with all his intelligence, is destroyed by pride. Alyosha, simple and loving, finds courage amid trials. Dostoevsky shows that a heart that loves Goodness is forged in virtue, even amid suffering.

The author does not ignore life’s desolation. Suffering is real and inescapable. Yet it’s precisely because of his honesty that his message resonates: learn to love Goodness, and no evil — not even Satan — can defeat you.

Alexei (Alyosha) Karamazov

Alyosha, meanwhile, feels called to the religious life, but his own superior in the monastery sends him back into the world, affirming that holiness should not be confined to cloisters but should radiate into everyday life. This is Alyosha’s mission: to sanctify the Karamazov family — a family viewed with disdain and contempt in their town.

Alyosha is a kind-hearted character; he represents the tangible possibility of grace in the world. He does not isolate himself from human misery but faces it with compassion, patience, and hope. His calling is not to flee but to be lovingly present.

Dostoevsky did not write this as a threat but as a statement of fact: without God, human beings become lost — like Ivan, who tries to live by reason alone and descends into despair; or like Dmitri, who seeks meaning in excess and reaps only destruction. Alyosha, even when surrounded by darkness, chooses the path of light. He shows us that holiness is not a privilege of monks nor an unattainable ideal — it is a possible, urgent, and real vocation.

So Alyosha is sent back into the world. His mentor dies, his heart is troubled, and then he understands — God does not call him to flee the world, but to sanctify it from within.

And this is where his story intertwines with ours.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: “The desire for God is written in the human heart” (§27). Alyosha feels this desire pulsing within him, but he also sees it suffocated within his own family. His father, Fyodor Karamazov, is a dissolute man, enslaved by pleasures and coarseness. Dmitri, the eldest brother, lives ruled by passions and disordered impulses. Ivan, the intellectual, carries an abyss within himself — he denies God but cannot bear a world without Him. Around Alyosha, chaos reigns. And it is precisely in this setting that he chooses not to flee, but to remain.

If we pay attention, these characters represent the world and its responses to the absence of God. Alyosha’s father is the portrait of depravity, while his brothers symbolise the paths the world offers: scepticism (in Ivan) or hedonism (in Dmitri). And it’s clear to see: the behaviour of both is contemptible in the relationships they build.

Alyosha, however, offers the counterpoint. He brings God into human relationships and into the world itself. His presence transforms those around him; his convictions are not imposed, but they resonate. And suddenly, the certainties of others begin to waver — because where God enters, everything can be renewed.